Please visit this site on a larger device.

Please visit this site on a larger device.

Chapter 2

Temperance and Prohibition

By Matthew J. Bellamy

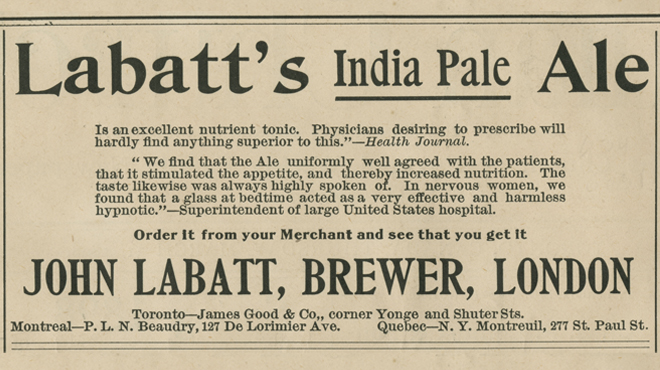

Beginning in the early nineteenth century, a temperance movement swept across the land. The movement’s advocates urged British North Americans to reduce their use of alcoholic beverages. At first the movement, which was largely made up of Anglo-Protestants, was not necessarily against beer. Indeed, due to its lower alcoholic content, beer was viewed as an ideal “temperance drink.” For example, in September 1828 one Canadian temperance tabloid, the Colonial Patriot, trumpeted: “On Friday last the frame of a large house… was erected WITHOUT THE USE OF RUM! In lieu of it, ale and beer were used, so that the work was completed in a superior manner, while neither abusive language, or profane swearing was heard, no black eyes nor drunken men seen.”

But as the century progressed towards its middle decades, the temperance movement became increasingly uncompromising. The “dry” stance shifted to a position of total abstinence: no hard liquor, wine or beer should be consumed. In November of 1848, the Canadian Temperance Advocate published an article written by “A Reformed Drunkard,” which warned of drinking’s slippery slope. “By sipping a little wine, beer, or cider, occasionally, our relish for strong drink was formed, and we now know, to our shame and sorrow that in this way our habits of intemperance began.” In the temperance literature of the period, beer was being blamed by the “drys” for causing debauchery, blasphemy, discord within the family, and even death.

The rise of the temperance movement did not go unnoticed by those who were closest to John Kinder Labatt. His father in-law Robert Kell, for instance, warned Labatt in 1854 about the possibility of new temperance laws restricting the production and consumption of beer. Thus, Robert Kell advised his son-in-law to give up brewing and turn “to tanning or candle and soap making.” But where others could see only adverse risk, Labatt perceived a business opportunity. Confident that London would continue to grow and that he would manage the future as carefully as he had the past, Labatt ploughed his profits back into the business during the second half of the nineteenth century.

During the First World War (1914-1918), the drys in Canada seized a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to end their fight with the wets. Groups like the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union had long maintained that liquor had to go if there was to be a dry heaven on earth. But despite the passion of their convictions, the drys were unable to win over a majority of Canadians prior to the onset of hostilities in Europe.

The Great War changed everything. Virtually everyone understood that the war overseas demanded a higher level of personal sacrifice at home. Temperance advocates tapped into this sentiment to advance their cause. As one prohibitionist poster in B.C. put it: “Is the sacrifice made by our soldiers for us on the battlefield to be the only sacrifice? The Bar or the War? That is the question of the hour.” With missionary zeal, the drys argued that “King Alcohol” was an enemy as great as any overseas weakening the nation from within and those who failed to abstain from tippling were hindering victory.

The patriot plea struck a chord with those Canadians who were looking for a long-distance way to martyr themselves by suffering something for the war that implied personal discomfort. As a result, beginning in 1916, one province after another adopted laws that prohibited the retail sale of “intoxicating beverages.” By 1918, Canada was dry from sea to sea.

According to the laws of the new dry regime, brewers like John Labatt were allowed to produce temperance beer – i.e. “non-intoxicating” beverages with no more than 2.5% proof alcohol. Labatt named its temperance beers Comet and Old London Brew. These “near beers” were not nearly as popular as regular strength beer and John S. Labatt noted “it is hard to market 2.5% beer except by peddling.”

With declining profit margins, Labatt engaged in a mail order business that saw Labatt’s full-strength beer exported to places where prohibition was not in force, like Quebec, and then and this was the ingenious twist shipped back into Ontario for private consumption. The innovative scheme complied with the letter of the law, although it infuriated prohibitionists. One indignant prohibitionist explained Labatt’s “shell game” in the following way: “The liquor is first put on a joy ride on a freight train to Quebec to become Frenchified and then it is sent back again to Ontario.” Faced with mounting pressure from the drys, Canada’s wartime Prime Minster, Robert Borden, put a halt to the practice in late 1916.

In the midst of prohibition, and with the financial losses mounting, the board of directors at John Labatt Ltd. decided on June 17, 1921 that “unless something very unforeseen occurs” it would shut down the historic brewery in the next year. Hearing the news, Labatt’s general manager Edward Burke, a hard-nosed Irishman who had cut his teeth selling tobacco and whiskey in the United States, made the board an offer that it could not refuse. Keep making beer and let me run things, Burke beseeched the board, and the brewery will survive prohibition. All Burke wanted in return was ten percent of the profits.

Having convinced the board of directors to soldier on, Burke began bootlegging beer and hard liquor to the United States, where the federal government had recently enacted national prohibition. The new strategy did not please everyone at Labatt. For instance, Hume Cronyn Sr. wrote to his wife’s nephew John S. Labatt in 1922, urging him to keep the business aboveboard. But the bootlegging continued. To get his liquor across the Great Lakes, Burke acquired three large fishing boats: the Agnes W, the Cisco, and the Brown Brothers. By Christmas 1923, the sale of export-strength beer accounted for eighty-nine percent of Labatt’s total beer sales.

By the time prohibition came to an end in Ontario in 1927, only fourteen of the forty-nine brewers that were in existence at the beginning of prohibition were still in operation. The doors of thirty-five Ontario breweries had gone dark. Across the nation, prohibition had a similarly devastating effect on a once vibrant industry. The personal fortunes of many brewers were lost, legacies vanished, and hundreds of well-paying jobs disappeared. But John Labatt Ltd. had thrived during the dry regime. Operating within the margins of the law, Burke turned Labatt into one of the most successful bootleggers in Canadian history.

A legacy of prohibition survives today in Ontario. In 1927, a year after the experiment ended, Ontario’s brewers worked together to develop and establish an efficient method for the distribution and sale of beer. They secured warehouse space and acquired a transport company, and by the end of the year, Brewers Warehousing Company Limited had 86 outlets in the province. This model of a privately-owned system is known today as The Beer Store.

Prohibitionism had never fully faded from the collective consciousness, although for most Canadians it had lost its lustre in light of the failed “noble experiment.” According to the Ontario brewers’ internal polls, in 1940, only six percent of the province’s population desired a return to a bone-dry state. But the same survey showed that nineteen percent of the population believed that it would be better to prohibit the sale of beer, wine and spirits during the Second World War.

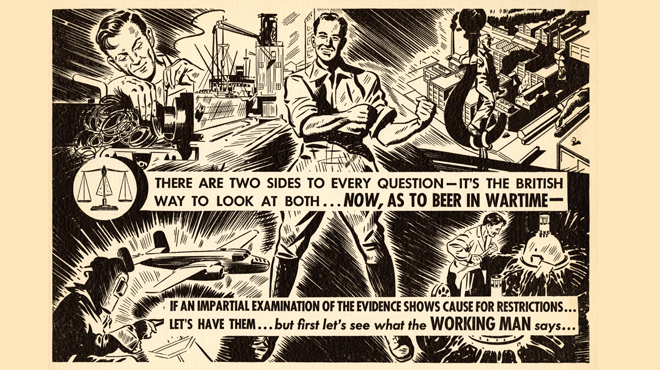

What was worse for those in the business of brewing was that there seemed to be growing support for stricter laws on the production and consumption of all types of liquor. After the outbreak of the Second World War, the leaders of the prohibition movement had begun tapping into this sentiment. And while the ultimate objective of the drys remained full-fledged prohibition, they were now more willing to wage a piecemeal campaign.

Across the nation, they lobbied for the closing of beverage rooms, the elimination of wet canteens, voluntary abstinence, and restrictions on beer production. Those at John Labatt Ltd., one of Canada’s oldest and most successful brewers, worried that “the public, in its present emotional state, might favour some form of anti-liquor legislation.” Even more worrying were the rumors that “the majority of the Members of the Federal Cabinet were inclined to favour Prohibition.”

In order to prevent the moral reformers from using the war as a lever to lift the lid off the tomb of prohibition, Labatt and its allies undertook a public relations campaign to convince Canadians that brewing and beer drinking were beneficial to the nation at war. In its advocacy ads, editorials, and “news items,” it used morally loaded messages to project the impression that brewing and beer-drinking were essential to the war effort. The beer lobby tapped into the underlying cultural logic of the age to sell beer-drinking as beneficial to the nation at war. The brewers aimed – and succeeded – at influencing public sentiment on the meaningfulness of beer during wartime and generating an unprecedented level of good will toward those engaged in the business of brewing.

Dr. Matthew J. Bellamy is an associate professor of history at Carleton University. He was the first researcher to fully utilize the Labatt Brewing Company Collection at Western Archives, and his work on the history of Canadian brewing has been published in The Walrus, Canada’s History Magazine, Legion Magazine, the Carleton Historical Review, Brewery History and the International Journal of Business History. In 2006, Dr. Bellamy won the National Business Book award, and he is currently working on a book-length history of Labatt.