Please visit this site on a larger device.

Please visit this site on a larger device.

Chapter 4

Here’s to the People

by Matthew J. Bellamy

When John Clare began to work for John Labatt II in 1894 there were fewer than forty employees at the London-based brewery. A fit young man of twenty-five, Clare started work as a cooper making the barrels that held the beer, but soon found himself doing a variety of physically-taxing jobs. Brewery work in the nineteenth century required muscle, dexterity and skill as men like Clare lifted and lugged raw materials and barrels of beer as part of their daily duties. At a time when few processes were mechanized, workers filled the bottles by hand using hoses connected to the barrels. The bottles themselves were washed, filled and corked by hand before the labels were put on by a worker with brush and a pot of gum tragacanth. Clare did this job along with many others during his forty-nine years with Labatt.

In 1910, when the engineer and watchman were both sick, John Clare worked for two days and nights without a break, coopering during the daytime and then tending the engines and boilers at night. “Those were the days when a night man had to fire all the boilers and turn a couple of hundred of barrels,” he later recalled.

The relatively small scale of the brewery’s operations in those days encouraged John Labatt II to cultivate close ties with his workers. As the boss at the brewery that bore his family name, he created a stable hierarchy based upon deference and mutual obligation. John Labatt II continued the tradition of building bonds between management and workers by arranging regular social events, like picnics and dances. He also gave his men bonuses and gifts. For example, during the holiday season he often footed the bill for food and drink. “Purchase at my expense for yourself,” he instructed one of his employees, “a nice turkey and take a couple of dozen ale for Christmas and charge same to me.” He was not alone in his approach to labour. Other brewers emulated his paternalistic business practices.

In August 1910, Labatt recognized Local 381 of the American Federation of Labor. “It is quite a victory for unionism in general,” proclaimed the Toronto Star. Collective bargaining to increase wages and decrease hours at the London brewery followed soon thereafter and resulted in the agreement of 1910. The agreement fixed the workweek at fifty-nine hours for the summer months and fifty-four hours through the winter. Wages were increased by twenty-five cents per week on the existing schedule of wages for the first year, and fifty cents per week for the second year.

In 1912, Labatt moved to three paid holidays per year and established a standard work-week of fifty hours all year round, a minimum weekly wage of $10.40, and full pay for four and a half holidays: New Year’s Day, Good Friday, Labour Day, Christmas Day, and “a Saturday morning to be arranged for an excursion.”

In 1913, John Clare succeeded Jack Steele as the president of Local 381. Under the terms of a new agreement, Labatt’s employees saw their wages increased to $13.00 or $14.00 per week, with coopers and engineers earning $18.00 as the most skilled men in the brewery. These figures represented an increase of twenty per cent since 1910. While such improvements could not have come without collective bargaining, they also depended on the financial health of the company and its ability to offset rising costs by increasing sales.

During the 1930s, a few progressive Canadian companies recognized that the remuneration of their workers should extend beyond the regular payment of wages and salaries to provisions for healthcare and retirement. Labatt was among this small group of enlightened companies. In 1938, President John S. Labatt stated that “the burden of hospital expenses is… a serious load for the individual to carry, and bills resulting from sickness many oftentimes take most of an individual’s savings.” As a result, the board of directors agreed on a plan for group life insurance and hospital benefits through the Aetna Insurance Company and a pension plan for its employees through the Annuities Department of the federal government in Ottawa.

The health plan gave employees three dollars a day while they were in hospital and provided them with an additional fifteen dollars to cover the cost of an operation if it was needed. The pension plan, on the other hand, provided for a degree of financial security after retirement. For every dollar paid by the employee into the pension plan, the company contributed a similar amount, up to 3% of each employee’s annual earnings. Labatt’s pension plan for all full-time employees won the labour movement’s praise.

On March 16th, 1943 John Clare became the first of Labatt’s employees to retire on a full pension under the Company’s Pension Plan. He was seventy-three years old and had worked for Labatt for forty-nine years.

No brewery, however well-equipped and managed, can expect to prosper unless it realizes that it has a responsibility to its employees that extends beyond their financial remuneration. In January 1939, The Canadian Beverage Review noted that “the interests and plans of the Labatt Company in its employees go far beyond any suggestion of legal obligations, they indeed take on the aspect of real human care and interest.” At Labatt there was a long-established tradition of empathy and understanding for its employees.

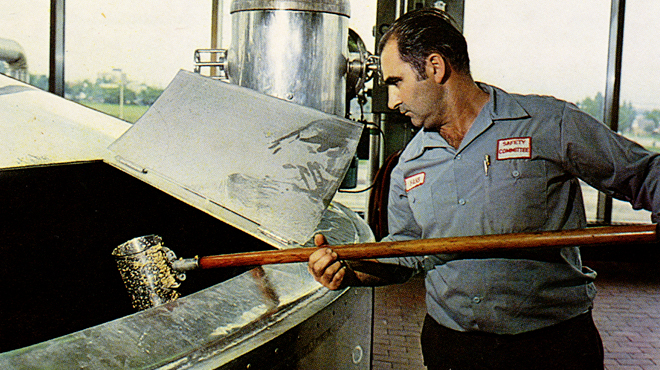

In 1943, Labatt made the working lives of its employees safer when it established the Safety Committee to promote accident prevention. One of the Safety Committee’s first recommendations was to hire a company nurse. In March of that year, the company acted upon the suggestion by hiring Marguerite Whitelaw. The wife of an Army captain who was serving overseas, Whitelaw was a registered nurse who had worked in one of Canada’s largest industrial plants during the previous six years. Professional and charming, Whitelaw worked under the supervision of the plant medical officer, Dr. Murray Simpson, and was responsible for “calling on employees who were confined to their homes because of illness or injury.” The same concern for its employees would later see the company introduce an Employee Assistance Program for alcoholism identification and treatment.

After the Second World War, Labatt’s general manager Hugh Mackenzie welcomed communication with the unions, hoping to anticipate grievances and resolve them around the bargaining table. In 1946, he met with the union and together they hammered out a contract that reduced a full-time employee’s time on the job to forty hours a week.

When Jake Moore became the first non-family president of Labatt in 1958, he continued the tradition established by Mackenzie of creating a working environment that was safe and respectful. Under his watch the company publicly declared that its philosophy in employee relationships was “to create a climate that will permit and encourage the employee to use their talents to the full and to obtain maximum individual satisfaction with their work.” This wasn’t just ideal talk. Labatt backed it up with concrete actions like being the first North American company in 1962, to guarantee an annual wage to its employees. Five years later it was among a small group of North American companies that extended ownership to its employees when it created the Employee Share Purchase Plan.

Shortly after prohibition came to an end in Ontario in 1927, J.R. “Doc” McLachrie joined Labatt to sell beer to the thirsty steel workers of Hamilton. At a time when beer drinking helped define working-class masculinity, McLachrie promoted Labatt’s products in “Hammer Town” by using all of the means at his disposal. Motivated by the potential of a hefty bonus, he drew down heavily on his expense account to generously treat customers in order to promote sales and brand loyalty. McLachrie succeeded in Hamilton by devoting time and energy to promoting Labatt’s products and by maintaining a personal presence in the community. On his day off, he would often attend leisurely events like picnics and baseball games.

Labatt’s salesmen like McLachrie took seriously their responsibility for stimulating sales. They worked long hours during the Great Depression for a salary of thirty-one dollars a week plus bonuses based on their sales. Labatt’s General Manager, Hugh Mackenzie, knew that the Liquor Control Board would not have approved of direct commissions, so the brewery developed an innovative system of bonus incentives instead. Salesmen then competed to be assigned to the biggest and most prosperous urban centres, such as Hamilton, where taverns sold relatively large quantities of beer.

After the Second World War, Labatt’s sales representatives visited a wide variety of drinking establishments. Some of them were quite nice. For example, the cocktail lounges that operated in all of the major urban centers were often lavishly decorated and furnished, and patrons often had to meet stringent dress codes, including shirt and tie for men and skirts for women. Other establishments weren’t so nice. Nevertheless, Labatt’s sales representatives visited them all. At a time when the industry was becoming increasingly consolidated, it was essential for Labatt to have a personal presence on the ground.

Back at the brewery, quality controls modeled on the best American breweries were introduced, and a small laboratory was created for research. The modern bottling shop ran twenty-four hours a day and, in 1953, produced enough bottles each month to cross Canada when placed end to end.

Workers took a great deal of pride in producing a popular product. By 1960, brewery workers were the highest paid industrial labourers in Canada. Added to which brewery work at Labatt was regular and secure, in part because the company had a practice of promoting from within. By 1962, Labatt had approximately 2,400 employees in Canada working at its nine breweries that were scattered across the nation.

During the 1980s and 1990s, the shock troops of the beer wars were the company’s beer reps, who generated sales through camaraderie, free T-shirts and footing the bill for theme nights.

At the end of the twentieth century, Labatt put into place measures that were designed to empower its employees to make a difference by taking action on their ideas. Through its unique Ideas Process, which was internally developed by unionized employees in 1999, employee-led Innovation Councils evaluated and implemented hundreds of employee suggestions every year.

By offering stable, high-paying jobs with good benefits and a merit-based bonus system, Labatt has been able to attract top-notch talent. These people in turn have raised the bar on industry standards and increased the firm’s efficiency. In the environmental arena alone, thousands of employee ideas have helped Labatt reduce its water, fuel and energy usage. Through the productivity and innovation of its people, Labatt has contributed to the economic prosperity of Canada.

As a result of these efforts, Labatt was named in 2014 as one of Canada’s Top 100 Employers. It has since been named to the Top 100 Employers list in 2015, 2016, and 2017. For three years running, beginning in 2015, Labatt has also been named one of Canada’s Greenest Employers and one of Canada’s Top Employers for Young People.

Dr. Matthew J. Bellamy is an associate professor of history at Carleton University. He was the first researcher to fully utilize the Labatt Brewing Company Collection at Western Archives, and his work on the history of Canadian brewing has been published in The Walrus, Canada’s History Magazine, Legion Magazine, the Carleton Historical Review, Brewery History and the International Journal of Business History. In 2006, Dr. Bellamy won the National Business Book award, and he is currently working on a book-length history of Labatt.