Please visit this site on a larger device.

Please visit this site on a larger device.

Chapter 7

Innovation and Inspiration

by Matthew J. Bellamy

Perhaps no city is more blessed by nature than London, Ontario when it comes to brewing. To make beer a brewer needs three essential ingredients barley, hops and fresh water. The rich alluvial flats in and around London are remarkable for their great fertility. As early as 1855, The Canadian Agriculturalist, a spirited farming newspaper, stated that: “It is not the city [i.e. London] alone that deserves mention for around it, on every side is spread out farming country of great beauty and fertility.” In addition to the rich soil, London is blessed with an abundance of fresh water. The geologic structure that underpins London is such that it infuses the water with carbonates and sulphates that enhance the brewing process. And yet it takes the artistry of a brewer to turn nature’s gifts into a perfect pint.

Before the scientific revolution in brewing occurred in the late nineteenth century, the art of brewing was handed down from brewmaster to apprentice over the generations. When Samuel Eccles taught John K. Labatt the art in the late 1840s, the brewing process started by making the barley malt. Barley grain was soaked in water for two days and then spread out on the floor for five days in order to let it germinate. Afterwards it was dried in an effort to halt the germination process.

The resulting product (i.e. the malt) was then cracked and crushed a process known as “milling.” This was done to make it easier for the malted grains to absorb water during the process of “mashing.” During this third stage of the brewing process, the milled malt was added to hot water to convert starch into fermentable sugars. Much like brewing tea, “mashing” released the sugars and flavours of the malt into the liquid. The next step in the brewing process the “lautering” was to strain the liquid out, separating it from the spent grain. The resulting substance was known as the “wort” a sweet liquid extract produced from the grains during mashing. The wort was the basis for the beer. John Labatt and Samuel Eccles then began the process of “boiling” the malt extracts i.e. the wort to ensure its sterility. The wort was then put back into the large copper pot to boil and the hops were added. Once the process of “boiling” was completed, the hops were strained from the wort and the liquid was cooled as the yeast was added. The yeast converted the brewing sugars into alcohol during the “fermentation” stage. The yeast did the hard work for the brewer, making the liquid into beer.

Part of the art of brewing was knowing when to stop the fermentation process at precisely the right time. If John Labatt halted the fermentation too high, the beer went into a vigorous secondary fermentation in the cask, making it cloudy and acidic. If, on the other hand, he attenuated the beer at too low a point, the beer became flat and lifeless. At that point, his only course of action was to throw out the bad beer and start again.

This was the art of brewing that Samuel Eccles passed it on to John Kinder Labatt, who in turn passed on to his son John Labatt Jr. Today the brewing process is fundamentally the same, although it is now more scientific and done on a much greater scale.

John Jr. brewed all of the beers of his father and one more. While he was a brewer’s apprentice in Wheeling, Virginia he learned the recipe for India Pale Ale (IPA). The invention of English brewers who were seeking to ship their beer to distant hot places like India, IPA was a top-fermented beer that used pale malt and had a considerably increased hop content. The result was a beer that was bitter-tasting, more alcoholic than other ales, and much lighter and brighter than the dark brown ales, porters and stouts that dominated the British North America beer market prior to 1870.

When John Labatt Jr. returned to his father’s brewery in 1864, he brought the recipe for IPA that he had learnt in the United States with him. The winner of numerous international awards, Labatt’s IPA was the brewery’s best-selling beer until the end of World War II.

In 1959, Labatt’s marketing managers met at Oakwood, Ontario to discuss the subject of national brands. Those at the conference had the foresight to realize that in the future “national brands” would dominate the market place and that huge savings could be achieved by promoting a single brand with a cohesive identity and advertising theme across the nation. At the time, a truly national beer brand did not exist in Canada.

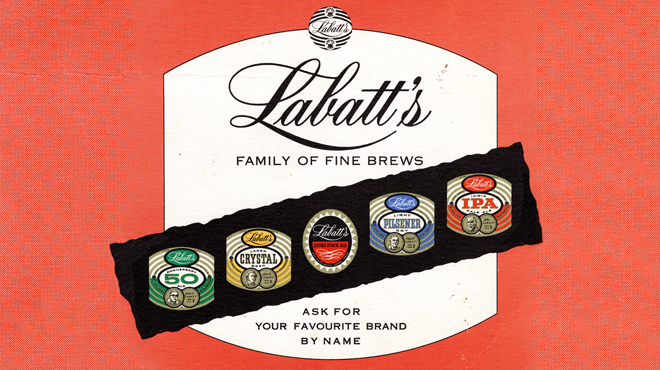

Labatt’s own line of beers in 1959 consisted of five brands: Crystal Lager, IPA, 50, Extra Stock Ale, and Pilsener. Labatt produced these brands along with the regional brands, which it had gained ownership of during its post-war acquisition phase. Given the trend towards milder tasting beer, the executives at Oakwood chose Pilsener to promote as its national lager and 50 to promote as its national ale.

But Pilsener had a difficult time gaining significant market share outside of Western Canada. Pilsener’s lack of appeal constituted what the marketing men at Labatt termed the “national lager problem.” The challenge was to broaden the image of the brand so as to appeal to the mass lager market.

In the mid-1960s, Labatt’s marketing executives began making changes to the firm’s flagship lager to make it more “Canadian.” They added the maple leaf, which had long been a symbol of the national identity, to the label. At the same time, they decided to rename the brand “Blue,” which was perfect because it picked up on a Western Canadian colloquialism and easily translated into French. In an effort to remind consumers of the company’s continued commitment to quality and tradition, the label also featured an image of the four gold medallions that the company had won at international competitions. The rebranding worked and Blue became Canada’s first national brand.

Labatt also had the distinction of being the brewer to bring light beer to Canada. In 1977, a senior Labatt executive, C.A. Stock, stated that “the times are right for a reduced calorie beer.”

Labatt introduced Special Lite in Ontario and British Columbia in December 1977. Special Lite’s brewing process did not use enzymes, but a natural yeast action that the brewery kept under wraps. The resulting brew contained 99 calories and 4.0% alcohol by volume.

Labatt Special Lite was subsequently renamed Blue Light, and became one of the best-selling beers in Canadian history.

The innovations continued during the 1980s. When Labatt did away with the stubby and replaced it with a new taller and slimmer bottle, it had one distinguishing feature, a twist-off top. A true product innovation, the twist off cap offered consumers an easy and convenient way of opening their beer by hand, without a bottle opener. These twist-top bottles helped give Labatt the lead in the fierce beer wars of the 1980s.

Labatt also had success with its Twist Shandy a beer and citrus flavoured drink with 2.3 percent alcohol by volume. The Twist Shandy provided Canadians with a tasty beverage that looked, poured and had the sociability of beer, but didn’t taste like it. The company also wanted to get back those customers who had switched to imported beer. To that end, Labatt launched Canada’s first premium beer, John Labatt Classic, in a distinctive bottle. Like the Twist Shandy, Classic successfully tapped into a niche segment of the Canadian beverage market.

Another product innovation was Ice Beer, which the company launched in 1993. The product emerged from years of R&D on freeze concentration. At a time when Labatt was looking to conquer export markets, the hope was that freeze concentration would shrink the volume of beer for transport. Once the concentrated beer arrived at its distant destination, it could then be mixed with water and brought back to its sale strength before packaging. It didn’t work.

Still the R&D did not go to waste. Executives at Labatt thought that the same technology might be used to produce “ice beer.” They believed the image of “ice” would appeal to Canadian drinkers, especially those who were already concentrating their beers by leaving the bottles outside in the snow or in the cold garage, essentially freeze concentrating them at home.

Labatt developed the technology to freeze the beer until ice crystals began to form. What made the ice process work was a series of high-speed wipers and agitators which stopped the beer from freezing solid as the temperature in the brewing tank plummeted. The result was a brilliantly clear and crisp lager that was slightly stronger than regular strength beer.

Labatt’s advertisements are a highlight reel of Canadian marketing. For almost two centuries, Labatt’s ads touched the Canadian psyche and communicated highly emotional messages in the blink of an eye.

John Labatt was in the vanguard of the advertising revolution in Canada. A humble and reserved man in private, Labatt displayed none of these characteristics when it came to publicly promoting his products. His marketing was unique among the brewers of the nation. He was one of the first to engage in brand-driven marketing. His ads clearly defined what was being promoted, who was doing the manufacturing and why the product was worth purchasing. This simple, yet clever innovation proved valuable to Labatt in the struggle to distinguish his ales and stouts in competitive markets across the land.

After prohibition came to an end in the 1920s, Labatt found it difficult to get its message out because all advertising had to conform to provincial liquor control board standards, which could range from controls on the content to outright bans. Within this restricted advertising environment, Labatt came up with ingenious ways to promote its products. One of the ways was to promote its brands in magazines like Maclean’s and Saturday Night that were published in Quebec where the restrictions on beer advertising were more slack but sold across the country. Another way was to give away promotional material, like calendars.

Whatever the medium, Labatt ads often featured images of people enjoying themselves in the outdoors. This was because the land held a special place in the hearts and minds of Canadians during the interwar period. The country-side was seen as a sanctuary from the problems of the city. The ads of the period thus featured the beer drinker fishing at a river, or hiking in the woods, or taking a nap in a park. Linking beer and beer-drinking to the land made it more appealing to mainstream Canadians.

At the same time, Labatt’s marketing mavens linked the evolution of the firm to the watershed moments in Canadian history, like Confederation and the Boer War, “when soldiers knew good ale.” At a time when Canadians were searching for uniquely Canadian ideas, events, experiences and commodities the makers of a national identity Labatt ads served up its product as an age-old piece of Canadiana.

In the post-war period, beer ads became ubiquitous. Beer drinkers and non-beer drinkers alike knew the catchphrases of the ads of Labatt, like “Take Five for Fifty Ale” or “Call for a Blue.” As a result, beer ads became part of popular culture.

During the 1950s, Labatt’s advertisements tapped into post-war notions of domesticity. For example, the ads for Pilsener featured middle-class couples in formal attire (and certainly not jeans and T-shirts), enjoying their lager in a cocktail lounge rather than a working-class beer parlour. The government’s regulations on beer advertisements kept the scenes being depicted in the tradition of romance and glamour. Other ads portrayed beer drinking as a reward from some challenge that had been met and overcome be it a hard day of work, or a tough game of sports.

During the “swinging sixties,” Labatt began marketing to those of the baby boom generation. At a time when popular culture was very youth-oriented, the people in Labatt’s ads were visibly younger than they were in previous advertisements. These youthful people were also situated in more casual settings. The ads of the late 1960s and early 1970s displayed relaxed, mixed-gendered socializing, with hints of the “swinging” singles lifestyles.

When colour television hit the Canadian scene, executives at Labatt knew that “Blue” would be a natural attention-getter on the screen if it were associated with the right jingle and moving images. This led to the famous “Blue Balloon” campaign, which successfully associated Blue with the concepts of happiness, escape, and relaxation.

The Blue ads that appeared in the 1970s and early 1980s featured men and women swimming, fishing or skiing and then relaxing around the campfire, often at a cottage. The commercials always finished with a view of a Blue balloon, followed by a quick shot of a foamy beer glass all accompanied by the line of music, “When you’re smiling, keep on smiling. Blue smiles along with you.”

In 1984, Labatt parted ways with its long-time advertising agency, J. Walter Thompson, and awarded the lucrative Blue contract to Scali, McCabe, Sloves. What had won Scali the contract was the firm’s “There’s a Heart in This Land” commercial pitch. Adopting a practice already established by Budweiser in the U.S., Scali proposed to use real people and not actors in the commercial. In addition, the theme song would be sung not by one of the usual Toronto studio voices, but by an unheralded Toronto tavern singer by the name of Paul Langiell.

When the new Blue commercial appeared in 1985, it featured hard working Canadian men and women a woman painting the dividing lines on a road in St. John’s, a dancer in a club in Montreal, a young male air marshal on a runway in Vancouver, and a musician in a bar in Winnipeg. In the background, Langiell’s husky voice belted out the catch refrain: “There’s a beat in this land, it’s there in all we do. That’s why hands across the country reach for the Blue.” The beer commercials of the 1980s were revolutionary in that they married the universal language of music with images of regular people working and having fun in the city.

The early 1990s saw Labatt launch several new brands, including Labatt Genuine Draft and Labatt Ice. To spearhead its advertising campaign for Ice Beer, Labatt hired Alexander Godunov, an expatriate Russian dancer better known to younger drinkers for playing one of the violent German terrorists who battled John McClane in the action movie Die Hard. The image makers at Labatt hoped that Godunov’s sculpted-granite features and grunting monosyllabic speech would bring the image-conscious young adults flocking to Ice. They were right. Labatt Ice quickly gained a large slice of the segment market.

As the twentieth century approached its end, Labatt revolutionized the image of its iconic Blue brand with the award-winning “Out of the Blue” campaign, including the well-remembered “Street Hockey” spot.

Labatt’s advertising campaigns of the 21st century extend far beyond the original mediums (i.e. T.V., radio and print). Through social media, such as Facebook, Twitter and YouTube, consumers are now empowered to share the Labatt marketing campaigns that are the most personally relevant to them with just a few clicks. In the digital age, technology not only makes these ad campaigns possible, it also significantly extends their reach and connects consumers with Labatt’s brands as never before.

Labatt has also designed marketing campaigns that tap into the consumer’s passion for brands, such as Budweiser, and the sports and music that fans most associate with them through real-life experiences that live on via social media. For example, the Budweiser “Red Light” campaign featured a goal light that was synched to flash red and sound a horn whenever the fan’s favourite hockey teams scored a goal.

Budweiser’s “Red Light” commercial resonated with beer drinkers across the country, as did the two-storey high Goal Light which was transported from New Brunswick to the North Pole. Along the way, fans were able to sign “Canada’s Goal Light” at various stops. Fans shared their excitement for Budweiser and Canada’s game face-to-face in homes, bars and stadiums and through social media. There are now more than over 50,000 Budweiser Red Lights across Canada.

Dr. Matthew J. Bellamy is an associate professor of history at Carleton University. He was the first researcher to fully utilize the Labatt Brewing Company Collection at Western Archives, and his work on the history of Canadian brewing has been published in The Walrus, Canada’s History Magazine, Legion Magazine, the Carleton Historical Review, Brewery History and the International Journal of Business History. In 2006, Dr. Bellamy won the National Business Book award, and he is currently working on a book-length history of Labatt.