Please visit this site on a larger device.

Please visit this site on a larger device.

Chapter 1

Three Generations of Labatt and the Brewery They Built

By Matthew J. Bellamy

In 1847, John Kinder Labatt went into partnership with Samuel Eccles and a brewery was born. Labatt had never intended to be a brewer. As a young man of modest means growing up in Ireland, his principal aspiration was to find a respectable job outside of the town of Mountmellick, where he was born in 1803. In 1830, he arrived in London, England, eager to make his mark in the world’s largest city. But due to his Irish background, he found it difficult to move up the ranks in the world of business. As a result, in 1834, he and his young wife, Eliza Kell, decided to begin a new life in British North America.

After a three-month journey, the Labatt family arrived in Upper Canada (present-day Ontario) in January 1834. Labatt wasted little time before staking his claim to 200 acres of land. For the next thirteen years John Labatt toiled in the fields of his farm, growing a variety of crops and tending to his livestock. But by 1846 he had become restless and was determined to find an enterprise that would satisfy his urge to be in business. He thus sold virtually everything he owned and returned to England.

In England, Labatt found it difficult to adapt, in part because he had made the trip without Eliza. In addition, England no longer felt like home and he worried that his time roughing it in the bush had handicapped his development. He was sure, however, that with the right business partner he could overcome any weaknesses gained while working in the fields.

When he was in England, Labatt’s thoughts often returned to his colonial homeland. “I often think when I am in the blues that I should be glad if I were settled in something amongst my old friends again… I fancy I should like brewing better than anything else…” Just a few months before, his old friend, Sam Eccles, had purchased the London Brewery on Simcoe Street from its original owner, John Balkwill.

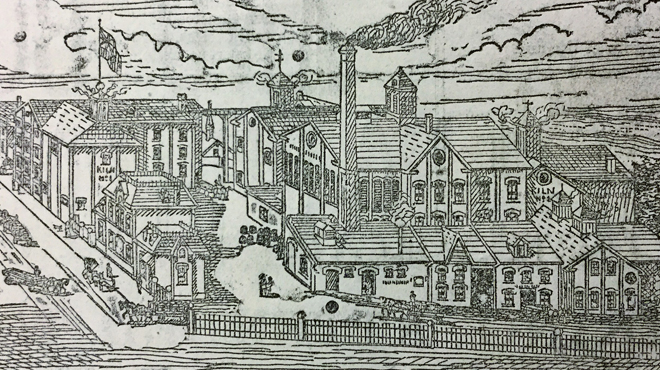

Established in 1828, the London Brewery had started in a small log and plank building on the banks of the Thames River not far from London’s core. A gambling man, Balkwill had seen his fortunes ebb and flow over the years, and he was often in desperate need of cash. Such was the case after the “great fire” of 1845, which reduced the London Brewery to a heap of ash and scorched rubble. Willing to take another chance, Balkwill rebuilt his brewery in stone the following year. It boasted a capacity of 2,500 barrels per annum.

Having overextended himself during reconstruction, Balkwill sold the London Brewery to Sam Eccles in February 1847. When the news reached John Labatt in England he lamented not being involved. Two weeks later, on April 16, 1847, with his mind made up, Labatt wrote to Eliza again, this time from Glasgow. “I have been considering this brewing affair for some time,” he wrote, “and I do think it would suit me better than anything else, for I fear very close confinement would not suit me after thirteen years of an active life in the open air.” The letter contained a detailed proposal for a partnership with Samuel Eccles.

Over the next six years, Labatt increasingly took on a dominant role in the brewery. As a result, the London Brewery became associated in the public mind with Labatt. Due to this, Eccles began to look for another business to enter. Confident in the future, Labatt offered to buy out Eccles at a price that reflected the fair market value of the brewery. Once the ink had dried on the bill of sale, John Kinder Labatt was the sole owner of the London brewery that to this day bears his family name.

In the years that followed, the small pioneer brewery of John Kinder Labatt grew to meet the growing demand for its beer from those near and far. John K. Labatt was one of the first to recognize that transportation was a key to industrial growth and business success. Shortly after the arrival of the Great Western Railway in 1853, Labatt began shipping his beer to agents in the largest central Canadian cities: Ottawa, Kingston, Hamilton, Toronto, and Montreal.

Unfortunately, John Kinder Labatt never witnessed the full effect of his business strategy. On October 26, 1866, he died of a heart attack, the result of a condition that had afflicted him for some years. The obituary that appeared in the London Free Press gave a detailed account of his struggles during his last days and concluded by noting that: “Throughout his career the deceased was remarkable for his energetic, shrewd and pushing business qualities.”

In his last will and testament, Labatt sought to structure his affairs so that the brewery he had founded would remain prosperous and, ideally, in family hands. According to the will, Eliza was entitled to keep the brewery, sell it, or lease it out to another brewer. But if Eliza chose to rent or sell the brewery, the offer must first go to their third son, John Labatt.

Eliza Kell had been John Labatt’s confidant, devotee, partner and life-long sweetheart. When the couple met in the spring of 1833, Eliza was seventeen, thirteen years younger than John Kinder Labatt. But Eliza Kell carried herself in such a way that did not reflect her young age. From the moment they met, Eliza provided Labatt with a sense of security and emotional support. Not surprisingly, he fell deeply in love with her and they soon were married.

At a time when women could not vote or own property, Eliza Kell Labatt worked behind the scenes to help her husband grow the brewery. Between 1835 and 1844, Eliza bore six children, four of them sons – Robert, Ephraim, John and George. She gave birth to a child almost every two years and by 1853 was raising a family of ten children. She was to bear four more before her last pregnancy in 1861, when she was forty-five. Tragedy occurred in 1858 when four of the children died from a local outbreak of diphtheria. In all matters, Eliza influenced her husband’s decisions. The two therefore agreed that the brewery was best left in the hands of their third eldest son, John Labatt.

More so than any other individual, John Labatt Jr. put the Labatt brewery on its modern footing. After his father’s death in 1866, he grew the London-based brewery to be one of the biggest in Ontario and its beers were internationally recognized for their superior qualities.

In terms of his approach to business, John Labatt was his father’s son. He was pragmatic, principled and forward-looking. He was paternal to his employees and honest, almost to a fault. But above all, like his father, he was proud of the beer that was being produced at the London-based brewery.

Growing up in a house situated on the brewery grounds, John Labatt was constantly surrounded by beer, brewers and beer drinking. While he received a formal education, he never talked about doing anything other than entering the family business. Thus, at the age of nineteen, John Labatt took up full-time employment at his father’s brewery. Two years later, in 1859, he journeyed to the U.S. to work as an apprentice brewer. When he returned in 1864, he was made the brewmaster and manager of his father’s firm.

As manager and brewmaster of the newly-named “Labatt and Company,” John Labatt made all the important strategic decisions. Like his father, he was willing to take reasonable risks in order to grow his business. In 1867, he introduced India Pale Ale (IPA) to the marketplace. It was an immediate success. Labatt sensed that beer tastes were moving away from heavy porters and stouts to lighter pale and amber ales. By century’s end, pale and amber ales constituted almost half of the Canadian beer market. At Labatt, IPA accounted for the bulk of production for more than three quarters of a century, from the 1870s to the end of World War II.

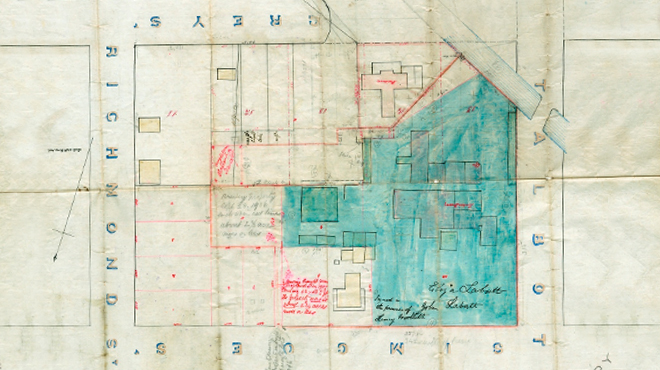

Between 1861 and 1870, production at Labatt’s brewery almost doubled from 3,000 barrels to 6,000 barrels of beer a year, substantially higher than at most other breweries in the province. With the profits flowing in, John Labatt decided to change the firm’s ownership structure. On August 15, 1872, after six years of partnership, and almost twenty-five years to the day since John Kinder Labatt entered the business of brewing, John Labatt bought out his mother’s interest in the brewery. The two partners agreed that the brewery had significantly appreciated in value since 1866 and was now worth $87,280. Eliza Labatt lent John Jr. the money necessary to purchase her half share in the brewery, in the form of two mortgages at eight percent interest per annum.

Disaster struck in 1874 when a fire burnt down the brewery. But John Labatt was quick to rebuild. When the reconstruction was completed, the new brewery was substantially larger than the old. The brewery had a capacity of 30,000 barrels a year, with storage space for 85,000 bushels of malt. In the months that followed, sales steadily increased due to his business strategy of manufacturing new, superior products and expanding his market.

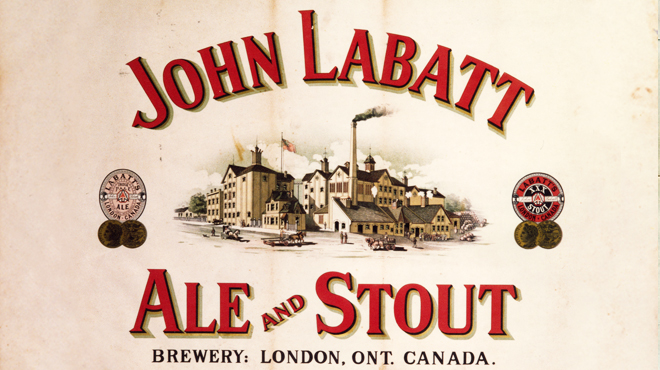

In 1876, Labatt decided to take on the competition at the 1876 World’s Fair in Philadelphia. Companies from around the world were attracted to the exhibition by the prospect of winning prizes and drawing attention to their products. In a world that had not yet witnessed the advent of electronic media, expositions like this offered manufacturers a medium through which to situate their products in the hearts and minds of the public. Brewers came from all over the world – Great Britain, Sweden, Portugal, Australia, India, the Netherlands, and many other places. Canadian and American brewers therefore faced stiff competition. But when the judging was done, Labatt had bested them all. While his XXX stout beer was pronounced by the international judging panel to be “first–rate,” his IPA was awarded a gold medal.

After the competition, Labatt seized upon the advertising opportunity that the victory gave him. In a series of advertisements that appeared in the press, he trumpeted his success in Philadelphia. At the same time, Labatt began including images of the medals in his ads.

Over the next three decades the brewery flourished despite price wars and government restrictions on the sale of intoxicating beverages. In 1911, the Labatt brewery sold almost $500,000 worth of beer. In a move to ensure continuity of ownership, in April 1911 John Labatt incorporated the firm, the last of the big Ontario brewers to do so. The new public corporation did away with private ownership and the separation of ownership from management. This was the hallmark of what the Harvard business historian Alfred Chandler has termed “managerial capitalism.”

On April 28, 1915, the headline in the London Free Press read, “MR. JOHN LABATT SUCCUMBS AFTER TEN DAYS’ ILLNESS.” At the time of his death, John Labatt was seventy-seven years of age and still the president of the firm that bore his name. John Labatt’s will specified that the company was to be carried on under the management of his two sons, John Sackville and Hugh Francis, and that their remuneration was “to be fixed by the other Trustees and not to exceed Two Thousand Dollars a year to each for the first four years after my death.”

At the time of John Labatt’s death, John Sackville was thirty-five years old, while his younger brother, Hugh Francis, was thirty-two. Of the two, John was the more genial. His university education made him better educated than his younger brother. John was a handsome man, with dark eyes and dark hair. He stood five-feet-eight-inches tall, and weighed about 165 pounds. He walked with a limp and later with a cane because one foot had been deformed in a boyhood accident. Hugh, on the other hand, was handicapped by a stutter that intensified his shyness. He had completed his secondary education at Trinity College School in Port Hope, but without sufficiently high grades to get into university. John, on the other hand, studied science at McGill and, after graduating, attended the U.S. Brewery Academy in New York.

John and Hugh impressed those they met with their graciousness and charm. As the historian Albert Tucker makes note, their stable and predictable reactions made it possible for workers to approach them without feeling intimidated. These attractive characteristics gave both men a spirit that had a positive impact on the company over the next three decades. The two brothers saw the brewery through World War I and prohibition.

The fact that the Labatt brewery prospered during prohibition when so many other breweries failed made John S. Labatt a target for kidnappers. Kidnapping was common during the darkest days of the Great Depression. Kidnappers targeted people who could command a “king’s ransom,” and few had prospered more than the beer barons who had survived prohibition. In 1934, John S. Labatt was one of the wealthiest brewers in Canada. At a time when many across the nation could not even afford the gas to run their cars, John Sackville was chauffeured around in a stately black limousine.

On August 14, 1934, three kidnappers pulled John Sackville from his car on a secluded gravel road just outside of London and ordered him to write a note to his brother. “Dear Hugh,” John wrote, “do as these men have instructed you… and don’t go to the police.“ On the other side of the note, the gang’s leader, Michael McCardell, a sharp-featured man of forty-two who had lost his index finger in a shoot-out with police, wrote: “We are holding your brother for $150,000 ransom. Go to Toronto immediately and register at the Royal York Hotel… You will know me as Three-fingered Abe.”

For three days, John Labatt remained blindfolded and chained near Lake Muskoka. When the kidnapping became front-page news, the bandits panicked and agreed to let Labatt go if he promised to pay them $25,000. At 12:30 am on Friday August 17, John Labatt was dropped off at the corner of Vaughan Road and St. Clair Avenue in Toronto, just a few miles northwest of the Royal York Hotel, where Hugh Labatt was stationed. John Labatt was free.

John and Hugh remained at the helm of the corporation during the 1930s and 1940s. In 1950, Labatt launched its “Anniversary Ale” to celebrate the fact that John Sackville and Hugh Labatt had been working at the brewery for fifty years. The beer was subsequently renamed “50” and became Canada’s best-selling ale.

Dr. Matthew J. Bellamy is an associate professor of history at Carleton University. He was the first researcher to fully utilize the Labatt Brewing Company Collection at Western Archives, and his work on the history of Canadian brewing has been published in The Walrus, Canada’s History Magazine, Legion Magazine, the Carleton Historical Review, Brewery History and the International Journal of Business History. In 2006, Dr. Bellamy won the National Business Book award, and he is currently working on a book-length history of Labatt.