Please visit this site on a larger device.

Please visit this site on a larger device.

Chapter 3

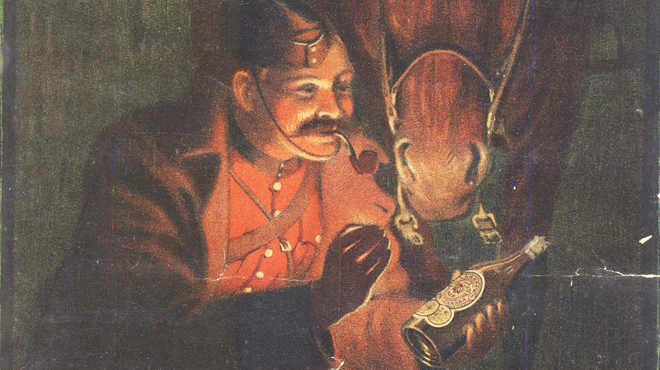

Supporting the Troops

by Matthew J. Bellamy

Beer has long been part of the soldier’s life. During the War of the Spanish Succession (1701-1714), the Commander of the British Forces, the Duke of Marlborough, proclaimed: “No soldier can fight unless he is properly fed on beef and beer.” British authorities accepted Marlborough’s statement as gospel, and in the years that followed British soldiers were given enough “beer money” to purchase five pints of beer a day. This stimulated the growth of the brewing industry in Canada, particularly in those places like London, Ontario, where British troops were stationed. Between 1838 and 1853, eight regiments, including the 32nd British Infantry, were stationed in John Labatt’s home town. The military loyally served Labatt. The troops stationed in London gladly handed over their pay packets in order to quench their thirst with the quality English-styled ales and stouts that Labatt made.

After Confederation in 1867, drinking and socializing became intertwined in many militia units. As it was ingrained in British tradition, there was no hesitation in providing beer to Canadian troops who fought under British command in the South African War from 1899 to 1902.

After the outbreak of the First World War on August 4, 1914, beer continued to play a role in maintaining the physical and spiritual well-being of the troops. Soon after their arrival in Britain in the autumn of 1914, Canadian troops began visiting the pubs in the little villages around Salisbury Plain. When the Canadian Expeditionary Force arrived in Europe in 1915, the drinking continued. Mess life revolved around having a beer at the bar, where soldiers had a brief chance to relax together, talk about events and loved ones back home, exchange raunchy jokes, and generally reaffirm their identities as fighting men.

Members of the Labatt family were some of the first to enlist in the Canadian forces. Two of John Labatt’s nephews, Dalzell Browne and John Chilton Mewburn, saw action on the western front. Dalzell Browne’s younger brother, George Sackville, was in the Royal Canadian Artillery. Robert Labatt, who had managed the brewery’s agency in Hamilton, was one of the first in the family to “see action.” John Labatt’s grandson, Verchoyle Cronyn, ended the war as a Canadian flying ace, while his granddaughter, Catherine Cronyn, served as a volunteer with the French Red Cross to help rehabilitate French citizens uprooted by the war.

The fact that so many of John Labatt’s relations were in the military convinced another one of his nephews, John Labatt Scatcherd, that he too should “be in it.” In February 1916, Scatcherd enlisted in the 3rd Brigade, Canadian Field Artillery. In letters home to his mother, Katharine Labatt, John always painted the rosiest picture of life on the western front. “Of course, we are lucky here,” he bravely wrote. “It is great satisfaction to feel that you are fighting and in the thick of things.” But men were falling, and falling fast, faster than the government could find new volunteers to replace them.

On September 3, 1918, John Scatcherd was acting as forward observing officer for his battery. Somehow his telephone got disconnected and so he left his bunker to find the break in the line. He did not return. He was later found, lying in a shell hole, with shrapnel in his leg and back. Posthumously, John Labatt Scatcherd was awarded the Military Cross for distinguished service in battle. Sadly, he was not the only member of the Labatt family to die overseas. John Chilton Mewburn and Dalzell Browne were also killed as young subalterns on the western front. As the family mourned the loss of those who had given everything to the nation in its time of need, the business of brewing continued at Labatt as the company limped under the weight of prohibition towards the peace.

Beer played a fortifying role again during World War II (1939-1945). John S. Labatt took pride in the fact that his brewery was supplying some “cold comfort” to the fighting men in the hot theatres of Europe, North Africa and East Asia. Soldiers like Warrant Officer B.A. Proulx were grateful to Labatt for contributing to the war effort.

After his escape from Hong Kong, Proulx was astonished to find that the drys were criticizing Labatt for supplying Canadian soldiers with beer. “It never occurred to us, while we were under fire by the Japanese,” Proulx protested, “that our people at home were waging a battle to prevent us from having something that we not only wanted but also sorely needed.”

During the Second World War, more than 20,000,000 gallons of Canadian beer was shipped to the troops overseas. Canadian beer helped those on the front lines cope with the toughest conditions. Beer calmed the nerves, relaxed the body, and uplifted the soul. It built bonds between the fighting men and helped carry the Allied nations through the war and on to victory.

On the home front, Word War II brought with it an acute shortage of beer. In part, the scarcity of suds was a consequence of Ottawa’s wartime policies. A life-long teetotaler, Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King believed that alcohol impaired “the efficiency of the fighting forces and the wartime workers of the country.” As a result, on December 16, 1942 he issued the Wartime Alcohol Beverage Order, which restricted the annual volume of beer sold by each brewery to not more than ninety percent of its sales in the previous year. At a time when breweries were operating at close to capacity, King’s order meant that less beer would be available for domestic consumption.

No other shortage brought more of an uproar during the war than the lack of beer. Canadians proved to be willing to put up with a virtual famine of other items. But the inability to get a glass of beer after finishing a day’s work was something that wartime workers and military men could not stomach. Their protests were many and often. In Vancouver, for example, angry shipyard workers threatened to boycott the sale of victory bonds if they did not get more of their favorite beverage. ”No Beer – No Bonds” was their battle cry. Across the nation, wartime workers and veterans signed petitions to register their disapproval of the beer restrictions. Although the medium took many forms, the message was always the same: “We want more beer.”

In May 1943, Mackenzie King finally addressed the problem by introducing rationing by coupon, which restricted the purchases of Canadians aged twenty-one years and over to twenty-four pints of beer per month. These controls on food and beverage consumption came on the heels of months of periodic shortages and a precipitous spike in prices.

But ration by coupon led to as many problems as it solved. A black market in beer coupons emerged, bootlegging became widespread, and Canadians continued to complain that they could not get enough beer. Facing mounting political and public pressure, Mackenzie King lifted the restrictions on beer on March 13, 1944. The Prime Minister had finally come to the conclusion that restricting the supply of beer was not “sufficiently important to the war effort to justify the risk of continuous misunderstanding and friction…”

Having fought for, and demonstrated, that beer was needed in times of war as well as peace, Labatt continued to supply Canada’s troops in the last half of the twentieth century. During the Korean War, Labatt sent its Anniversary Ale which was subsequently renamed “50” to the Canadian troops who were fighting for the United Nations. Almost 27,000 Canadians served in Korea during the combat phase (1950-1953) and the peacekeeping phase (1953-1957). The troops were grateful for the gift. Korea was a tough war in which to participate.

There were many other dangers that could destroy an army and leave it unfit to fight. In addition to the possibility of losing one’s life, being injured or captured, there were the challenges of extreme boredom, homesickness and withering morale. Korea was as difficult a country as any in the world in which to station great bodies of troops whose only task was to watch and wait. A beer break passed the time and fostered new friendships between the troops while they were away from home. So grateful were Canadian soldiers to Labatt for sending shipments of beer that some took the time to put pen to paper to state that they were “enjoying your most welcome gift of Anniversary Ale.”

The tradition continued in the years that followed, with Labatt sending its beer to Canadian troops in Cyprus, Egypt, Israel, Syria and a number of other places where Canadians were attempting to keep the peace. During the First Gulf War, managers and workers at Labatt launched “Project Oasis.” The initiative saw employees at Labatt donate their monthly allotment of beer to the Canadian Forces personnel serving overseas.

Dr. Matthew J. Bellamy is an associate professor of history at Carleton University. He was the first researcher to fully utilize the Labatt Brewing Company Collection at Western Archives, and his work on the history of Canadian brewing has been published in The Walrus, Canada’s History Magazine, Legion Magazine, the Carleton Historical Review, Brewery History and the International Journal of Business History. In 2006, Dr. Bellamy won the National Business Book award, and he is currently working on a book-length history of Labatt.