Please visit this site on a larger device.

Please visit this site on a larger device.

Chapter 8

Labatt Legacy

by Matthew J. Bellamy

They have been making beer at Labatt since 1847, when John Kinder Labatt – an Irish immigrant of Huguenot stock joined Samuel Eccles in the business of brewing. During the brewery’s formative years, the partners exploited the region’s rich supply of natural resources to make quality British-style ales and stouts. These craft brews were copiously consumed by the military and civilian populations in London, Ontario most of whom could trace their ancestry back to the great beer-drinking nations of England, Scotland and Ireland. Labatt prospered enough to be able to buy out Eccles in 1853.

In the years that followed, John Kinder Labatt was one of the first Canadian brewers to seize the opportunities of the age of steam, steel and rail, by using the railroad to ship his beer to various outlets across the colony/province. When his third eldest son John Labatt took over the business in 1866 he followed the strategy established by his father, ploughing the profits back into the business in order to expand the scale and scope of his production. He rarely borrowed from outside sources and promoted his finely-crafted brews with missionary zeal.

By using the railway to ship his products to agents in distant regional markets, John Labatt II helped initiate a sharp turn towards market integration and essentially set the course for the rise of large regional breweries and the gradual decline of small locally oriented ones at the end of the nineteenth century. These years also saw John Labatt II become the first Canadian brewer to establish a physical presence outside of the national boundary when he began bottling his award-winning beer in the United States.

During the first half of the twentieth century, Labatt continued to grow in large part by making what the Harvard business historian, Alfred Chandler, describes as a “three-pronged investment” in production, managerial organization, and distribution and retailing networks. During the dark years of prohibition, Labatt not only survived but thrived by shipping its beer to the United States. After the “noble experiment” came to an end, Labatt played a major role in creating a culture that celebrated beer as quintessentially “Canadian.” More so than any other brewer, Labatt made Canada into a nation of beer drinkers. As a result, today, beer is to Canada what wine is to France. It is a symbol of our Canadian-ness.

At the end of WWII, Labatt became a publicly traded company. While the capitalization of the company remained the same, the number of shares was increased from 90,000 to 1,000,000. The sale of shares raised a total of $3.6 million. In the company’s first annual report, John S. Labatt acknowledged the contribution of the new and the old shareholders “who risked capital in order to provide the plant and equipment necessary to produce the commodity which the Company sells.” The corporate restructuring marked the beginning of the modern Labatt corporation.

In 1945, Labatt was one of the largest brewers in the nation. Eager to maintain the firm’s standing in the industry, executives reflected on what was needed to succeed in the post-war world. They concluded that in order to survive, it was necessary to “go ahead to become truly national.”

At the end of WWII, the Canadian brewing industry was made up of sixty-one breweries, and together they brewed 159 brands. Yet not a single brewery or beer brand was “truly national.” All that changed after the war as Labatt gained a physical presence in every major region across the land.

Having smoothly transitioned into a publicly traded company, Labatt gained the access to capital it needed for growth in the post-war period. There were plenty of opportunities for brewers who could think imaginatively and act aggressively. The post-war economic boom brought with it an unprecedented demand for beer. On this backdrop, Labatt embarked upon an aggressive strategy of growth by way of geographic expansion.

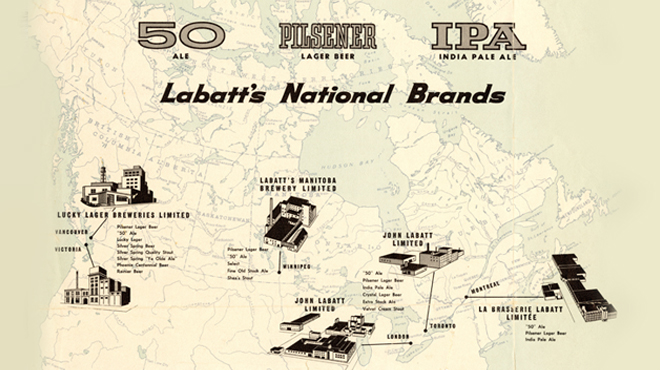

The nature of Canada was such that it was impossible for Labatt to become “truly national” from its base in Ontario. Beer was a bulky and heavy commodity in relation to its selling price and transportation expenses constituted a large portion of Labatt’s production costs. In addition, provincial governments had instituted tariffs and imposed import quotas that limited out-of-province beer or stopped it from flowing altogether. To be a truly national brewer, therefore, Labatt had to have breweries in provinces across the nation. As a consequence, between 1952 and 1962 Labatt purchased breweries in Ontario, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, British Columbia and Newfoundland and built new brewing facilities in Alberta and Quebec – the latter of which was used to supply beer to consumers in the Maritime Provinces.

In this market, advertising became essential for survival. Labatt’s success lay in the fact that it was able to create two new hugely popular national brands – Pilsner (later renamed Blue) and 50. The advent of television in the late 1940s further elevated the marginal benefits of advertising for Labatt. The enormous outlay necessary to market national brands was an important factor in the consolidation of the Canadian brewing industry between 1945 and 1970.

By 1970, Labatt controlled almost forty percent of the Canadian beer market and along with Molson and Carling O’Keefe were known as the “big three.”

During the 1970s, Labatt joined the legion of companies that were diversifying into new areas of production. Canadian corporate managers believed that having “all your eggs in one basket” was a dangerous strategy. At the peak of its diversification drive in the 1980s, Labatt had acquired the pasta maker Catelli, Chateau-Gai wines, Omstead Foods, which was the world’s largest processor of freshwater smelt, the juice maker Everfresh, two of the largest dairy companies in Canada and the U.S. in Ault Foods and Johanna Farms, and the grain processor Ogilvy. It also owned the Blue Jays, TSN, the Discovery Channel, Le Reseau des Sports, which was an all-sports French-language channel, and a number of other firms. In total, during the 1980s Labatt spent over a billion dollars to acquire more than thirty businesses.

At the same time, Labatt continued to expand its brewing operations. Labatt had long wanted to gain a presence in the Maritimes, where the population took delight in downing locally-brewed brands such as Schooner and Alexander Keith’s IPA. The problem for Labatt was that all of the Maritime Provinces had a tariff on out-of-province beer, which cut into its profits. As a result, Labatt began to study the feasibility of buying a Maritime brewery.

Early in 1971, Labatt got word that the owners of Oland & Sons Brewery the brewer of Schooner and Alexander Keith’s IPA were seeking to sell. The Oland family was one of the nation’s oldest brewing dynasties. The family had been brewing since Confederation. In 1928, the Olands purchased the Alexander Keith’s Brewery. Keith’s was the oldest brewery in the Maritimes and its acquisition put Oland & Sons in the enviable position of having a monopoly on brewing in Nova Scotia.

Having come to know the Oland family very well, the head of La Brasserie Labatt in Quebec, Tom Kirkwood, worked out the terms of the deal. After the takeover, Labatt energetically promoted its flagship brands – 50 and Blue – across the Maritimes. In 1974, Labatt acquired the Columbia Brewing Company in B.C., the maker of the popular west-coast beer, Kokanee. The takeover of Oland & Sons and Columbia Brewing further fueled the emergence of Labatt as a major Canadian corporation.

As the 1970s came to an end, there was a growing sense that in the future there would be a convergence of tastes and a globalization of brands. “We predict that the brewing industry will one day be dominated by a few huge breweries and a handful of global brands,” stated Don McDougall, the company’s President in 1979, “and think being ahead of everyone else might be a good idea.” Having joined Labatt after receiving an MBA from the University of Western Ontario in 1961, McDougall quickly moved up the ranks. Between 1973 and 1979, he held the titles of President and Senior Vice President and was a driving force behind the licensing agreement with Anheuser-Busch to brew Budweiser in Canada.

Having signed a ninety-nine-year license to brew Bud in Canada, Labatt rolled out the product in Alberta and Saskatchewan in the summer of 1980. The following year Labatt made Bud available to beer drinkers in Ontario, Quebec and British Columbia. By 1982 Budweiser had captured roughly seven percent of the Canadian beer market. Executives at Labatt were thrilled. “Bud’s success in this large section of the industry’s market has been nothing short of phenomenal,” stated Sid Oland, who had succeeded McDougall as President of Labatt in 1980.

In the mid-1980s, Labatt expanded into Europe. In October 1986, Labatt announced a corporate restructuring to create Labatt Breweries of Europe, to be headquartered in London, England. Shortly thereafter, Labatt launched a multi-million-dollar advertising campaign to promote Canadian Lager in Britain, using the tagline “Malcolm the Mountie always gets his can.”

As the gale winds of globalization gained force after 1990, a number of multi-national enterprises began eying the lucrative Canadian beer market. For these global firms, the goal was to enhance the promotion of local and regional brands while simultaneously introducing their “global brands” to the marketplace. The approach was pioneered by Belgium’s Interbrew SA, which had been making beer in Europe since 1366. In 1995, their debt-free, family-controlled company was Europe’s fourth-largest brewer, with sales of more than $2 billion.

In the early 1990s, Interbrew began acquiring breweries in emerging markets such as Romania and southern China. At the same time, it set its sights on the $30 billion North American beer market. But Interbrew’s big brands, Stella Artois and Jupiler, were virtually unknown to North American beer drinkers at the time. As a result, Interbrew’s executives decided that it was impossible to penetrate the highly competitive North American market through exports alone. Thus, in April 1995, Interbrew offered to acquire Labatt for $2.7 billion, or $28.50 per share.

Once the deal had been approved by the shareholders, Interbrew quickly set Labatt on a course to get “back to the basics.” As Interbrew’s Belgium-based spokesman Gerard Fauchey noted: “It’s very simple. We’re brewers, not managers of hockey or baseball teams or television stations.”

In 2004, Interbrew merged with AmBev, which was Brazil’s largest brewery, to create InBev, the world’s largest brewer. The merger gave InBev an unparalleled global platform to build on Interbrew’s strength in Europe, Asia and North America, and AmBev’s unrivalled position in Latin America. Four years later, InBev acquired the maker of the “King of Beers,” Anheuser-Busch. The deal brought together the world’s two largest brewers to create the global leader in beer. The mega mergers continued in, October 2016, when Anheuser-Busch InBev announced the successful completion of its combination with SABMiller. The third largest merger in human history was valued at US $123 billion and gave AB InBev a larger presence in developing markets like China, South America and Africa.

While its parent company was growing globally, Labatt continued to act locally, serving the interests of its stakeholders and enriching Canadian culture and society. In June 2011, Labatt donated two of Canada’s most significant collections of historical corporate archival materials and art to the University of Western Ontario and Museum London. The rich collections are of great national value and profound cultural significance.

But the business of brewing has not stopped. In 2015, Labatt added to its portfolio of brands, when it purchased the award-winning craft brewer, Mill Street Brewery of Toronto and the brewer of the Stanley Park family of brands, B.C.’s Turning Point Brewery. In Quebec, Labatt entered into a partnership in 2016 with Archibald Microbrasserie, a Quebec craft brewer renowned for its local beers and seasonal specialty brews.

Two thousand and seventeen marks Labatt’s 170th year in business. While much has changed since the pioneer brewery days, those at Labatt remain committed producing quality beers, supporting Canadian communities, contributing to the growth and development of the economy, and shaping Canadian culture and heritage.

Dr. Matthew J. Bellamy is an associate professor of history at Carleton University. He was the first researcher to fully utilize the Labatt Brewing Company Collection at Western Archives, and his work on the history of Canadian brewing has been published in The Walrus, Canada’s History Magazine, Legion Magazine, the Carleton Historical Review, Brewery History and the International Journal of Business History. In 2006, Dr. Bellamy won the National Business Book award, and he is currently working on a book-length history of Labatt.